1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is taken into account probably the most notable international disaster (1). The extremely contagious nature of the illness, usually with asymptomatic circumstances, poses a critical impediment to the healthcare system (2). Infections can propagate via human contacts inside households, communities, or randomly among the many basic inhabitants (3). The WHO declared COVID-19 a public well being emergency of worldwide concern on January 30, 2020, resulting in its immediate recognition. Subsequently, on March 11, 2020, it was declared that COVID-19 had transitioned right into a pandemic (4). Iranian governmental departments confirmed the preliminary case of a optimistic SARS-CoV-2 an infection on February 19, 2020. The SARS-CoV-2 virus has impacted greater than 7.6 million people in Iran, leading to over 146,480 reported fatalities as of August 2023 (5).

Previous analysis signifies that the adversarial impacts of the pandemic on financial situations, hospitalization, psychological well being, and subjective well-being fluctuate amongst individuals (14, 15). Studies spotlight disparities in subjective well-being and employment stability primarily based on people’ employment conditions, with these variations intensifying in the course of the pandemic (16, 17). Gender imbalances are strengthened as females usually tend to expertise job loss and diminished earnings, exhibiting decrease job efficiency than males (18). Education stage influences people’ responses to social insurance policies, with lower-educated people responding extra vigorously (19).

COVID-19 additionally has implications for youngsters’s well-being, impacting them via variations in help from their households (20, 21). While there are exceptions, socially advantaged people (corresponding to males) could also be extra adversely affected (22), contributing to the exacerbation of pre-existing social imbalances (23). The pandemic not solely intensifies present social inequalities but in addition creates new social distinctions (24). Additionally, there may be proof that COVID-19 danger elements are geographically distributed disproportionately, exhibiting an inclination for cluster patterns in areas outlined by rural, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic facets (25). Socioeconomic standing is taken into account a related consider each particular person sickness and the unfold of the illness (26). Past epidemics have proven that adversarial well being outcomes are extra prevalent in low socioeconomic standing teams on account of inadequate healthcare entry, unfavorable residing situations, and academic boundaries (27).

Iran has been one of the vital severely affected nations all through the COVID-19 pandemic. It is a big and complicated nation with vital disparities in public well being and socio-economic situations, making the spatial unfold of the virus throughout provinces multifaceted and with no singular rationalization. Mortality dangers are typically larger for older males, whereas younger adults and ladies face larger dangers of an infection. The pandemic has been notably extreme within the poorest and most unequal areas of Iran, such because the western provinces. These areas have skilled a excessive variety of infections and elevated mortality dangers on account of their disadvantaged socioeconomic standing and insufficient healthcare situations (28).

2 Materials and strategies

2.1 Study design and information assortment

2.2 MC

“The MC is the x and y coordinates of all of the traits of the examine space. We used it to seek out out the distribution adjustments or to check the distribution of the COVID-19 illness in response to the next equation:

X=∑i=1NXiN,Y=∑i=1NYiN

Where Xi and Yiare the coordinates of options and N is the whole variety of options” (11, 31).

2.3 SD

It exhibits the dispersion of the COVID-19 illness across the imply, which is obtained from the next equation (11, 31):

SD=∑in(xi−X)2¯n+∑in(yi−Y)2¯n

2.4 SDE

“The SDE is an acceptable software for displaying the dispersion ranges of a set of factors and is calculated as follows (11, 31):

SDE=varxcovxycovyxvary=1n∑i=1nx¯i2i∑i=1nx¯iy¯∑i=1nx¯iy¯i∑i=1ny¯i2

the place

varx=1n∑i=1nxi−xx2=1n∑i=1nx¯i2covxy=1n∑i=1nxi−x¯yi−y¯=1n∑i=1nx¯iy¯ivary=1n∑i=1nyi−y¯2=12∑i=1ny¯i2

Where xi and yi are the options coordinates, x¯ and y¯ are the meancenters, and n is the same as the whole variety of options. The rotation angle is calculated via the next equation” (13, 29). Where xi and yi are the deviations of the options from the MC. “The normal deviation of the rotation angle can also be calculated via the next equation (11, 31):

σ1,2(∑i=1nx¯i2+∑i=1ny¯i2±∑i=1nx¯i2−∑i=1ny¯i2)2+4(∑i=1nx¯y)2¯2n12

2.5 Moran’s I

“Moran’s spatial autocorrelation evaluation software examines spatial autocorrelation primarily based on the placement of two attribute values of geographic options. This software exhibits that the distribution sample of those options, contemplating the worth of the attribute below examine, has a cluster or scattered sample. This evaluation evaluates the distribution sample of options in house by concurrently contemplating the placement and the function. The outcomes of this evaluation present whether or not options are randomly scattered or clustered in house” (13, 29). Moran’s I is obtained from the next equation (11, 31):

I=nSo∑i=1n∑j=1nwj,izizj∑i=1zi2So=∑i=1n∑j=1nwi,jZI=I−EIVI

the place

EI=−1/n−1VI=EI2−EI2

Where zi is exhibiting the deviation of the function distribution from the imply xi−X¯, wi, j indicated spatial weight between the options i and j, n is the same as the options complete quantity, and s0 is the weights sum (11, 31).

3 Results

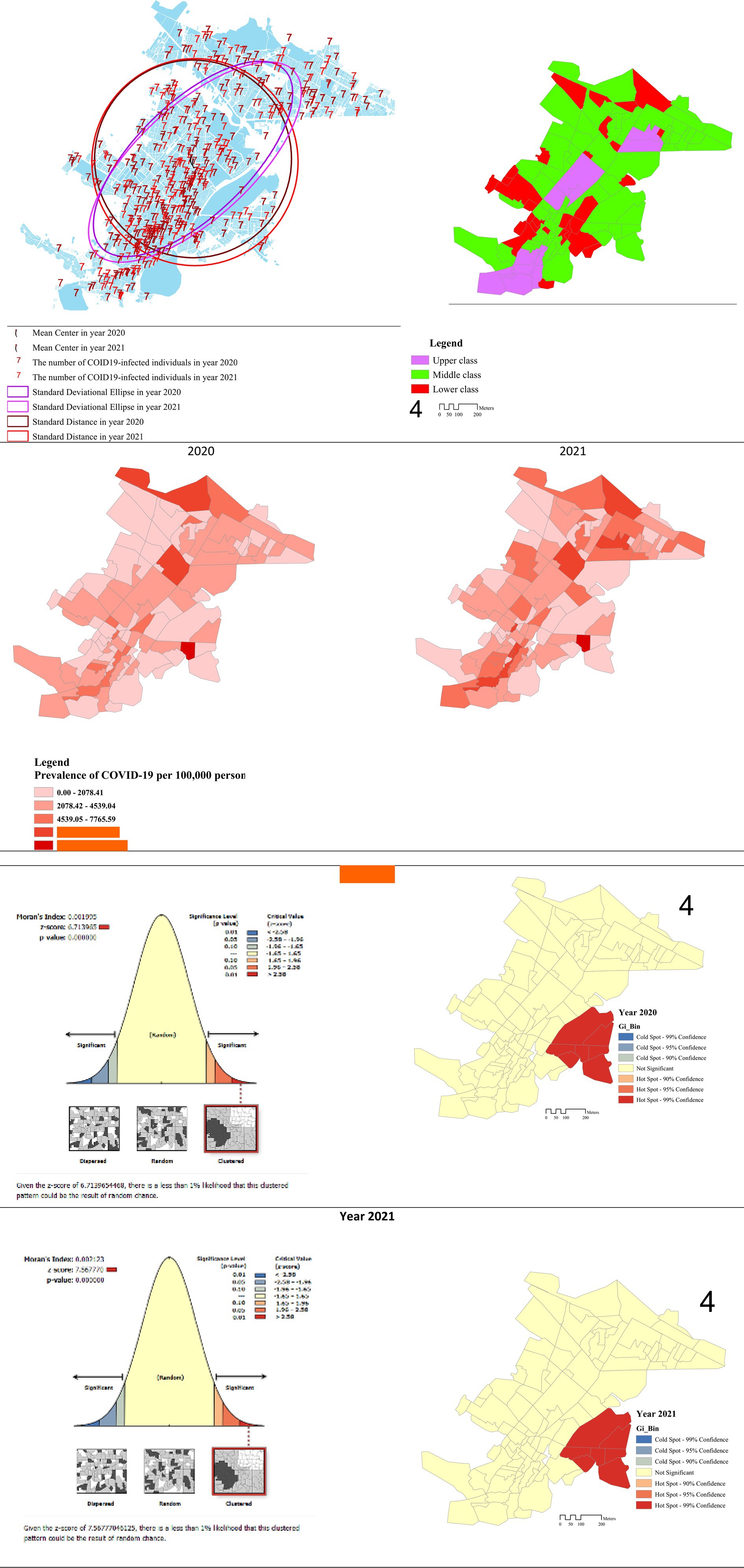

Our examine indicated that the MC of the illness shifted from town middle between 2020 and 2021, relocating to the jap a part of town in 2021. Notably, over 70% of the sufferers have been concentrated on this particular space, as illustrated in Figure 1. The outcomes concerning the SD unfold of the illness all through town, notably when evaluating 2020 to 2021.

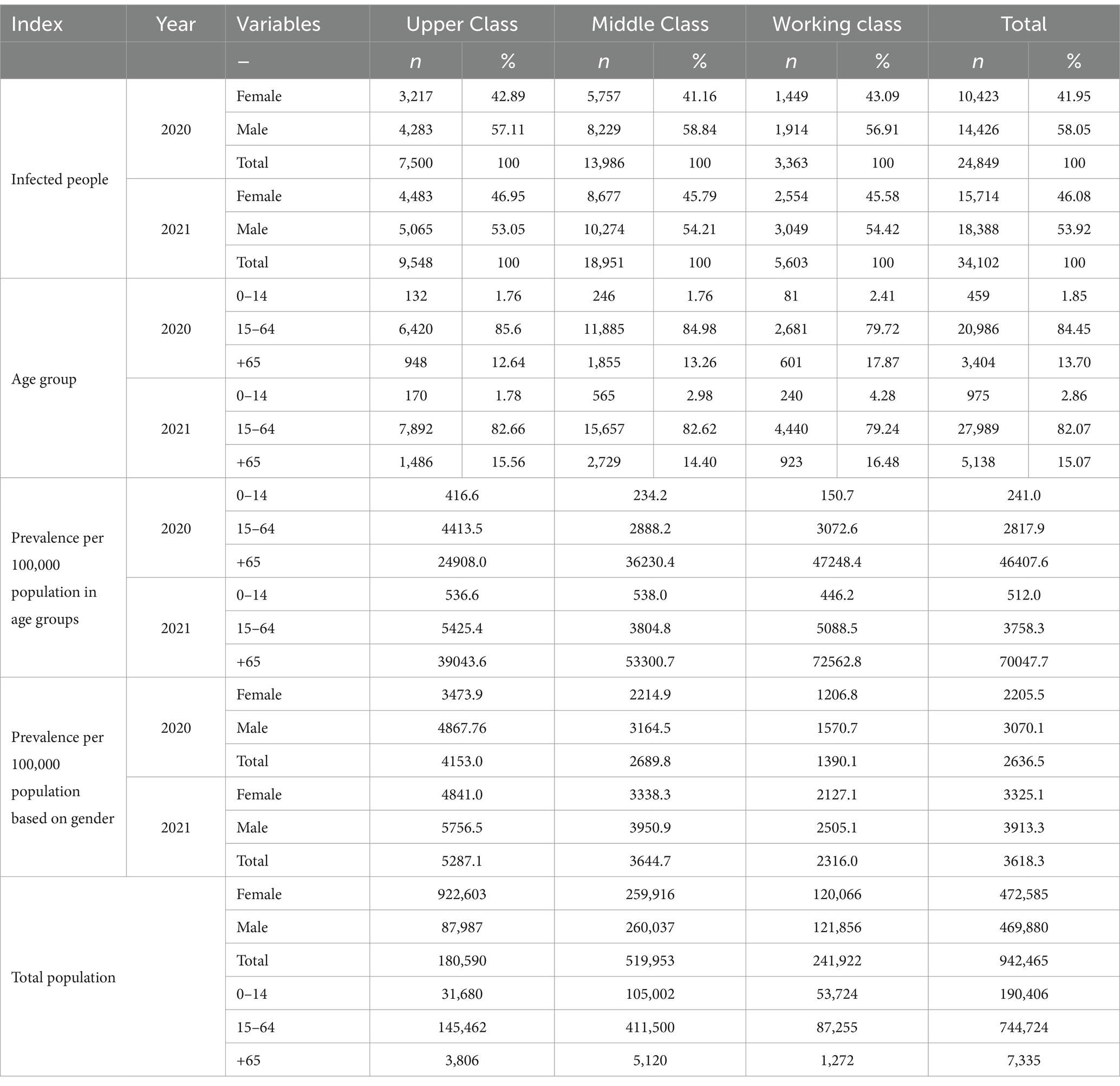

Figure 1. Spatial sample of the COVID-19 illness in Kermanshah metropolis among the many social lessons primarily based on assessments of SD, MC, SDE, and Moran’s I.

The SDE of the illness additionally exhibited a northeast-southwest route, and a comparability over the studied years demonstrated a rise in each the peak and a change in route of the ellipse in 2021 (Figure 1). Moran’s I spatial autocorrelation and the hotspot check have been employed to look at the spatial sample of COVID-19. The outcomes unveiled the formation of a clustered sample of the illness all through the studied years. Specifically, in 2020, the Moran’s I worth was 0.001, and it elevated to 0.002 in 2021, indicating the next prevalence of the illness in localized clusters. This means that the distribution sample of COVID-19 within the Kermanshah metropolis has exhibited clustering because the onset of the illness, with the depth of clustering growing over time (Figure 1).

The Global Moran’s I outcomes are offered within the left column figures. Figure 1 illustrates comparatively related clusters of COVID-19 in 2020–2021. In each years, Moran’s I values have been better than zero (0.001995, 0.002123) with excessive significance ranges (p-values: 0.001) and corresponding z-scores of 6.713965 and seven.567770 for the respective durations talked about. These findings point out a major spatial clustering of COVID-19 circumstances, emphasizing the consistency and statistical significance of the noticed patterns throughout each years. The outcomes of the hotspot check are offered in the best column figures. The Hotspot evaluation classifies polygons into seven distinct classes: three chilly spots (indicated by a unfavourable z-score) at confidence ranges of 99, 95, and 90%, in addition to three hotspots (indicated by a optimistic z-score) on the similar confidence ranges. Lastly, there’s a class the place the variations will not be statistically vital. Each of those seven classes is represented utilizing distinct coloration schemes, offering a complete visualization of the spatial distribution of COVID-19 clusters and non-significant areas.

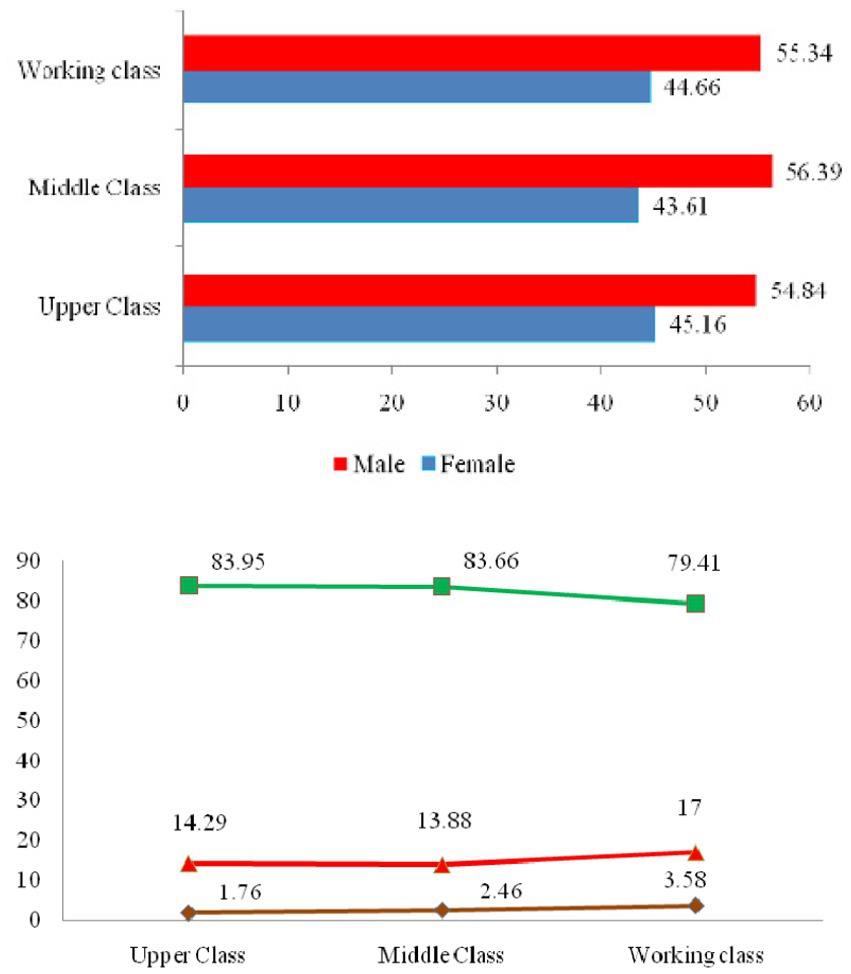

In this examine, 58,951 individuals within the Kermanshah metropolis have been contaminated with COVID-19, of which 32,874 (55.76%) have been males and 26,077 (44.24%) have been females. 28.86% have been within the higher class, 55.95% have been within the center class, and 15.19% have been within the working class (Table 1).

Table 1. Number of COVID-19-infected individuals, categorized by gender in age and gender teams among the many social lessons of the Kermanshah metropolis in 2020–2021.

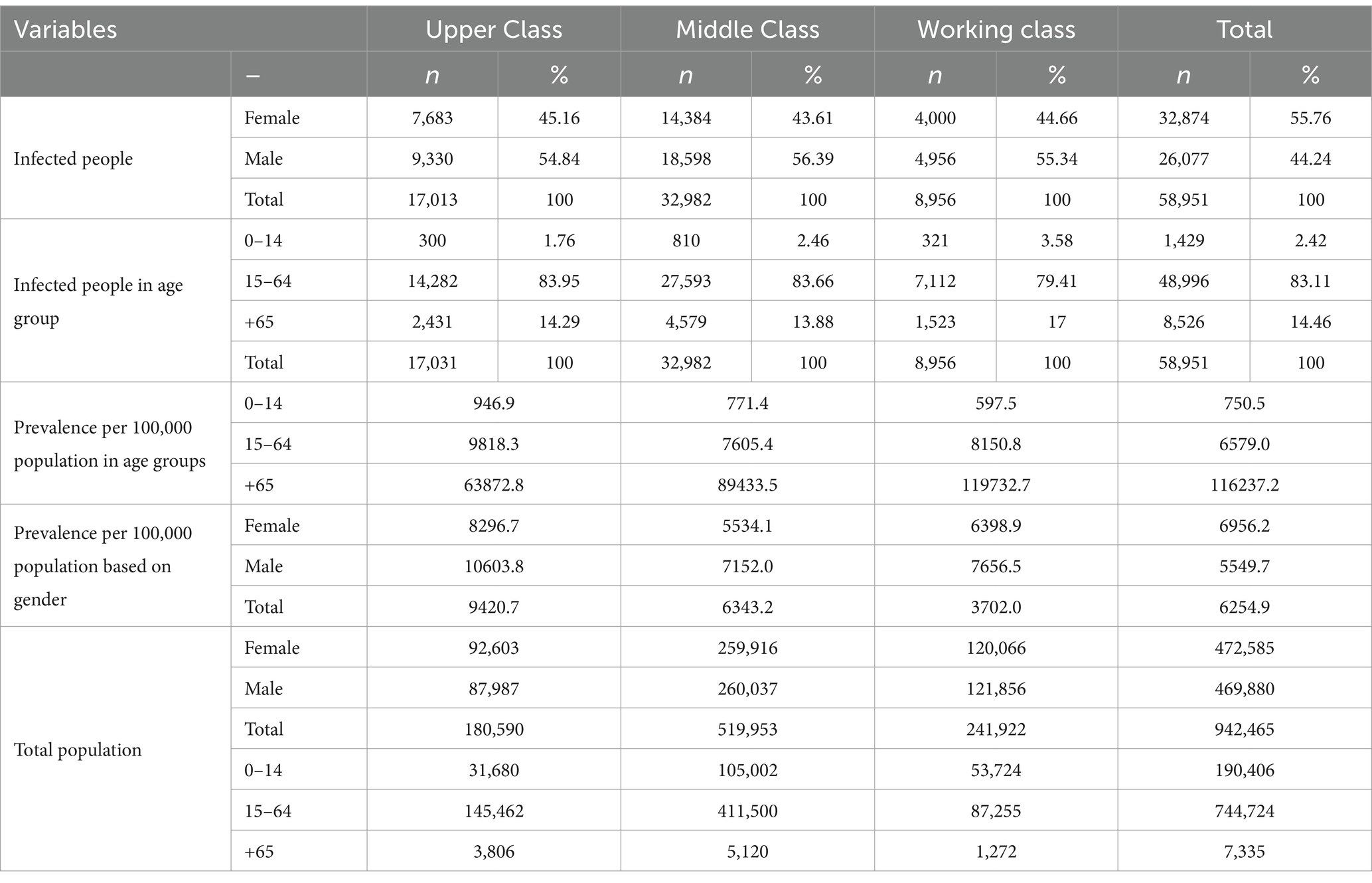

The outcomes indicated the next prevalence of COVID-19 in males in comparison with females. Furthermore, inside completely different social lessons, the illness was discovered to have the next prevalence amongst each women and men within the higher class in comparison with different social lessons. The information confirmed that in 2020, COVID-19 had the very best prevalence amongst upper-class kids, whereas in 2021, the very best prevalence was noticed in middle-class kids. In the age group of 15–64 years, the very best prevalence of the illness was discovered within the higher, working, and center lessons, respectively. But within the older grownup age group, the working class exhibited the very best prevalence. Overall, the findings demonstrated that the prevalence of COVID-19 within the older grownup was larger than in different age teams (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Table 2. Number of contaminated individuals by COVID-19, by gender in age and gender teams amongthe social lessons of the Kermanshah metropolis in 2020–2021.

Figure 2. COVID-19 circumstances categorized by gender and age teams throughout completely different social lessons within the Kermanshah metropolis.

4 Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a major risk and precipitated in depth hurt, particularly in city areas. Therefore, this analysis explores the spatial and temporal unfold of COVID-19 outbreaks and identifies high-risk areas throughout varied social strata inside the city space of Kermanshah.

Our examine confirmed that the MC of the illness shifted away from town middle throughout this examine interval. Over 70% of the sufferers have been concentrated in a selected space. SD of COVID-19 circumstances highlighted a major clustering of sufferers on this area, indicating a notable unfold of the illness all through town. The SDE of the illness additionally exhibited a northeast-southwest orientation, and a comparability over time studied demonstrated a rise in each the magnitude and a change in orientation of the ellipse. Other research have proven a powerful optimistic correlation between illness incidence and revenue inequality in addition to median family revenue in these areas. These socioeconomic disadvantages and inequalities exacerbated in the course of the pandemic; COVID-19 is not any exception. As the illness continues to unfold, the world has witnessed vital vulnerabilities in healthcare methods, a pointy financial downturn, and rising unemployment charges. For occasion, within the United States, those that lose their jobs are prone to dropping their medical insurance protection, additional exacerbating present well being and financial disparities (32). This pandemic has created a suggestions loop (32, 33).

The outcomes of this examine indicated that the COVID-19 illness within the Kermanshah metropolis exhibited a cluster sample because the onset of the illness, and over time, the depth of this clustering has elevated. Similar outcomes have been noticed in different research, indicating that no matter its waves, COVID-19 tends to type in clusters (34). Notably, the incidence of COVID-19 in kids confirmed a excessive price within the early phases with a household cluster sample, with contaminated kids usually being asymptomatic carriers and vital contributors to the illness’s unfold inside communities (35). In these areas, clusters of impoverished communities are marked by diminished median revenue, restricted employment alternatives, and decrease academic attainment ranges. Areas with decrease incomes, a comparatively excessive inhabitants density, decrease academic attainment, and the next unemployment price present a focus of COVID-19 infections (36). Furthermore, different research have emphasised that figuring out illness clusters is essential for recognizingat-risk facilities that require focused interventions and different public well being measures (37). This underscores the significance of understanding and addressing the clustered nature of COVID-19 for efficient public well being methods.

The outcomes indicated the next prevalence of the illness in males in comparison with females, aligning with related findings from earlier research (38, 39). The elevated prevalence in males is likely to be attributed partially to the next burden of pre-existing illnesses and occupational publicity. From an immunological perspective, females might exhibit a extra lively immune response, probably providing safety in opposition to infectious illnesses in comparison with males. This enhanced immune response is believed to be a results of higher responses to pathogens on account of larger estrogen ranges in females (37, 40). A examine carried out in Beijing confirmed that though COVID-19 had equal prevalence in women and men, contaminated males, no matter age, have been extra weak to experiencing extra extreme penalties and mortality (39).

A comparability of the illness prevalence amongst social lessons within the Kermanshah metropolis confirmed that the prevalence in females and males of the higher class was larger than in different social teams. Previous research have indicatedthat the unfold of COVID-19 in wealthier populations could also be related to leisure actions (41). Therefore, wealthier teams might exhibit more practical leads to an infection management by limiting leisure actions (34). It is believable that within the Kermanshah metropolis, the enforcement of quarantine insurance policies and associated authorities restrictions might have offered the higher class with the chance for elevated engagement in leisure actions, contributing to the upper illness prevalence on this social class. On the opposite hand, different research have acknowledged that “because the poor might have restricted entry to well being services, they might stay in the neighborhood with out remedy or hospitalization, interacting with others, growing the chance of illness transmission. Another perspective posits that people with decrease socioeconomic standing, usually characterised by decrease literacy ranges, might beless prone to get vaccinated. This inhabitants would possibly underestimate the optimistic results of vaccination or overestimate the dangers related to it, probably contributing to the next prevalence of the illness in the neighborhood (42). Studies have proven that socioeconomically deprived persons are not essentially vulnerable to the illness, however when they’re contaminated, their communities are at better danger of widespread illness transmission (34).

Our analysis findings make clear that the prevalence of the illness within the older grownup of the working class was larger than that of different social lessons. The older inhabitants has been recognized in quite a few research as a considerably significant factor within the unfold of COVID-19 (43, 44). Mansour et al. (2021) confirmed {that a} statistically vital correlation between the incidence of COVID-19 in Oman and the inhabitants over 65 (44). Moreover, poverty and an ageing inhabitants have been the contributing elements to the COVID-19 pandemic’s unfold all through European nations. Monitoring these vital variables can enhance the situation and cut back illness incidence (45). Friesen et al. (2020) demonstrated that the poor are weak to infectious illnesses. Their examine highlighted that elements corresponding to excessive constructing density, crowded residing situations, and poor well being contributed to the restricted implementation of well being measures and insurance policies in impoverished neighborhoods (46). Research has additionally proven that socioeconomic variables, notably poverty, may considerably improve the prevalence of COVID-19 (36). Due to restricted monetary sources, people in poverty might face boundaries in accessing healthcare services, probably remaining untreated or hospitalized and persevering with to work together inside the neighborhood, thereby growing the chance of illness transmission. Another speculation means that decrease schooling ranges amongst impoverished populations might end in decrease vaccination charges, with people underestimating the advantages or overestimating the dangers related to vaccines, thereby exacerbating the unfold of the illness inside the neighborhood (33).

The findings point out that in 2020, the illness had the very best prevalence amongst upper-class kids, whereas in 2021, middle-class kids exhibited the very best prevalence. Consistent with different research, COVID-19 prevalence in prosperous communities tended to be larger amongst kids. However, it’s essential to notice that kids can current a excessive prevalence of danger elements for extreme decrease respiratory tract infections. Shifting sources away from little one healthcare to deal with epidemics amongst adults might exacerbate the affect on childcare. The outcomes spotlight worrisome oblique results of the epidemic on kids’s well being, together with elevated poverty, disruptions in schooling, insufficient entry to high school feeding packages, interruptions in vaccination, and diminished entry to healthcare services and different kids’s well being packages.

4.1 Limitations

5 Conclusion

Spatial strategies are worthwhile for figuring out varied distribution patterns and hotspots of illnesses, in addition to detecting vital danger elements. COVID-19 manifested with a pronounced clustering pattern in city Kermanshah from the onset of the outbreak, with clusters intensifying over time. Substantial disparities in COVID-19 prevalence amongst completely different social lessons have been noticed all through Kermanshah in the course of the pandemic. Therefore, enhancing entry to digital healthcare information and spatial evaluation strategies holds appreciable potential for policymaking. These findings can information policymakers in implementing needed measures to fight infectious illnesses throughout completely different social strata.

Data availability assertion

Ethics assertion

The research involving people have been permitted by this examine obtained moral clearance and approval from the Ethics Committee at Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences for this examine. The moral reference code assigned to this analysis is IR.KUMS.REC.1400.228. The research have been carried out in accordance with the native laws and institutional necessities. The individuals offered their written knowledgeable consent to take part on this examine. Written knowledgeable consent was obtained from the person(s) for the publication of any probably identifiable photographs or information included on this article.

Author contributions

AlZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal evaluation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. NH: Data curation, Formal evaluation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. ZK: Data curation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. ArZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal evaluation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. HM: Formal evaluation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Software, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. ZGK: Data curation, Formal evaluation, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. RT: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal evaluation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. FK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. ES: Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – evaluate & enhancing. MS: Methodology, Visualization, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Writing – evaluate & enhancing.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflict of curiosity

Publisher’s notice

References

1. Pollard, CA, Morran, MP, and Nestor-Kalinoski, AL. The COVID-19 pandemic: a world well being disaster. Physiol Genomics. (2020) 52:549–57. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00089.2020

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Balcan, D, Gonçalves, B, Hu, H, Ramasco, JJ, Colizza, V, and Vespignani, A. Modeling the spatial unfold of infectious illnesses: the GLobal epidemic and mobility computational mannequin. J Comput Sci. (2010) 1:132–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jocs.2010.07.002

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Tabish, SA. Covid-19 pandemic: rising views and future tendencies. J. Public Health Res. (2020) 9:1. doi: 10.4081/jphr.2020.1786

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

6. Chowell, G, and Rothenberg, R. Spatial infectious illness epidemiology: on the cusp. Springer (2018). p. 1–5, 16. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1184-6

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Steele, L, Orefuwa, E, Bino, S, Singer, SR, Lutwama, J, and Dickmann, P. Earlier outbreak detection—a generic mannequin and novel methodology to information earlier detection supported by information from low-and mid-income nations. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:452. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00452

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Harapan, H, Itoh, N, Yufika, A, Winardi, W, Keam, S, Te, H, et al. Coronavirus illness 2019 (COVID-19): a literature evaluate. J Infection Public Health. (2020) 13:667–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.03.019

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Carroll, LN, Au, AP, Detwiler, LT, Fu, T-c, Painter, IS, and Abernethy, NF. Visualization and analytics instruments for infectious illness epidemiology: a scientific evaluate. J Bio Inform. (2014) 51:287–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2014.04.006

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Reshadat, S, Zangeneh, A, Saeidi, S, Khademi, N, Izadi, N, Ghasemi, SR, et al. The spatial clustering evaluation of HIV and poverty via GIS within the Metropolis of Kermanshah, Western Iran. Acta Med Mediterranea. (2016) 32:1995–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2024.102675

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Reshadat, S, Zangeneh, A, Saeidi, S, Teimouri, R, and Yigitcanlar, T. Measures of spatial accessibility to well being facilities: investigating city and rural disparities in Kermanshah, Iran. J Public Health. (2019) 27:519–29. doi: 10.1007/s10389-018-0966-9

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Khademi, N, Reshadat, S, Zangeneh, A, Saeidi, S, Ghasemi, S, Rajabi-Gilan, N, et al. A comparative examine of the spatial distribution ofHIVprevalence within the metropolis of Kermanshah, Iran, in 1996−2014 utilizing geographical data methods. HIV Med. (2017) 18:220–4. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12416

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Khademi, N, Reshadat, S, Zanganeh, A, Saeidi, S, Ghasemi, S, and Zakiei, A. Identifying HIV distribution sample primarily based on clustering check utilizing GIS software program, Kermanshah. Iran HIV AIDS Rev. (2016) 15:147–52. doi: 10.1016/j.hivar.2016.11.003

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Westrupp, EM, Stokes, MA, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M, Berkowitz, TS, Capic, T, Khor, S, et al. Subjective wellbeing in dad and mom in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. J Psychosom Res. (2021) 145:110482. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110482

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Bakkeli, NZ. Health, work, and contributing elements on life satisfaction: a examine in Norway earlier than and in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Population Health. (2021) 14:100804. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100804

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Dias, FA. The racial hole in employment and layoffs throughout COVID-19 within the United States: a visualization. Socius. (2021) 7:237802312098839. doi: 10.1177/2378023120988397

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. King, MM, and Frederickson, ME. The pandemic penalty: the gendered results of COVID-19 on scientific productiveness. Socius. (2021) 7:23780231211006977. doi: 10.1177/23780231211006977

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Choi, J, Park, Y, Kim, H-E, Song, J, Lee, D, Lee, E, et al. Daily life adjustments and life satisfaction amongst Korean school-aged kids within the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:3324. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18063324

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Yoosefi Lebni, J, Ziapour, A, Mehedi, N, and Irandoost, SF. The position of clerics in confronting the COVID-19 disaster in Iran. J Relig Health. (2021) 60:2387–94. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01295-6

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Hossain, M. Gender variations in experiencing coronavirus-triggered financial hardship: proof from 4 growing nations. Res Soc Stratificat Mobility. (2021) 71:100555. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100555

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Hu, Y. Intersecting ethnic and native–migrant inequalities within the financial affect of the COVID-19 pandemic within the UK. Res Soc Stratificat Mobility. (2020) 68:100528. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100528

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Qian, Y, and Fan, W. Who loses revenue in the course of the COVID-19 outbreak? Evidence from China. Res Soc Stratificat Mobility. (2020) 68:100522. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100522

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Khan, MM, and Odoi, EW. Geographic disparities in COVID-19 testing and outcomes in Florida. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14450-9

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Stojkoski, V, Utkovski, Z, Jolakoski, P, Tevdovski, D, and Kocarev, L. (2020). The socio-economic determinants of the coronavirus illness (COVID-19) pandemic. arXiv:200407947. doi: 10.1016/j.seps.2021.101083

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Sachedina, N, and Donaldson, LJ. Paediatric mortality associated to pandemic influenza a H1N1 an infection in England: an observational population-based examine. Lancet. (2010) 376:1846–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61195-6

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Pouyan, S, Bordbar, M, Khoshoui, MM, Rahmanian, S, Farajzadeh, Z, Heidari, B, et al. COVID-19: an evaluation on official reviews in Iran and the world together with some comparisons to different hazards. Computers Earth Environ Sci : Elsevier; (2022). p. 635–654. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10183-3

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. Reshadat, S, Zangeneh, A, Saeidi, S, Izadi, N, Ghasemi, SR, and Rajabi-Gilan, N. A feasibility examine of implementing the insurance policies on growing start price with an emphasis on socio-economic standing: a case examine of Kermanshah Metropolis, western Iran. Soc Indic Res. (2018) 140:619–36. doi: 10.1007/s11205-017-1790-2

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Ghasemi, SR, Zangeneh, A, Rajabi-Gilan, N, Reshadat, S, Saeidi, S, and Ziapour, A. Health-related high quality of life in casual settlements in Kermanshah, Islamic Republic of Iran: position of poverty and notion of household socioeconomic standing. Eastern Mediterranean Health J. (2019) 25:775–83. doi: 10.26719/emhj.19.013

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Reshadat, S, Saedi, S, Zangeneh, A, Ghasemi, S, Gilan, N, Karbasi, A, et al. Spatial accessibility of the inhabitants to city well being centres in Kermanshah, Islamic Republic of Iran: a geographic data methods evaluation. EMHJ. (2015) 21:389–95. doi: 10.26719/2015.21.6.389

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Gangopadhyaya, A, and Garrett, AB. Unemployment, medical insurance, and the COVID-19 recession. Health Insurance. (2020) 1–8. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3568489

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Mollalo, A, Vahedi, B, and Rivera, KM. GIS-based spatial modeling of COVID-19 incidence price within the continental United States. Sci Total Environ. (2020) 728:138884. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138884

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Chung, GK, Chan, S-M, Chan, Y-H, Woo, J, Wong, H, Wong, SY, et al. Socioeconomic patterns of COVID-19 clusters in low-incidence metropolis, Hong Kong. Emerg Infect Diseases. (2021) 27:2874–7. doi: 10.3201/eid2711.204840

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Seyedi, SJ, Shojaeian, R, Hiradfar, M, Mohammadipour, A, and Alamdaran, SA. Coronavirus illness 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in pediatrics and the position of pediatricians: a scientific evaluate. Iran J Pediatr. (2020) 30:e102784. doi: 10.5812/ijp.102784

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Siljander, M, Uusitalo, R, Pellikka, P, Isosomppi, S, and Vapalahti, O. Spatiotemporal clustering patterns and sociodemographic determinants of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) infections in Helsinki, Finland. Spatial Spatio-Temporal Epidem. (2022) 41:100493. doi: 10.1016/j.sste.2022.100493

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Ahasan, R, and Hossain, MM. Leveraging GIS and spatial evaluation for knowledgeable decision-making in COVID-19 pandemic. Health Policy Technol. (2021) 10:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2020.11.009

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Patil, A, Tripathy, JP, Deshmukh, V, Sontakke, B, and Tripathi, SC. SeXX and COVID-19: Tussle between the 2 (2020) 20:442–7. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0348-8

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Liu, S, and Yang, J. Gender variations in sufferers with COVID-19: concentrate on severity and mortality. Front Public Health. (2020) 8:152. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00152

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

40. Klein, SL, Dhakal, S, Ursin, RL, Deshpande, S, Sandberg, Okay, and Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Biological intercourse impacts COVID-19 outcomes. PLoS Pathog. (2020) 16:e1008570. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008570

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Wong, NS, Lee, SS, Kwan, TH, and Yeoh, E-Okay. Settings of virus publicity and their implications within the propagation of transmission networks in a COVID-19 outbreak. Lancet Region Health-Western Pacific. (2020) 4:100052. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100052

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Mollalo, A, and Tatar, M. Spatial modeling of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy within the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2021) 18:9488. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18189488

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Sun, P, Lu, X, Xu, C, Sun, W, and Pan, B. Understanding of COVID-19 primarily based on present proof. J Med Virol. (2020) 92:548–51. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25722

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Mansour, S, Al Kindi, A, Al-Said, A, Al-Said, A, and Atkinson, P. Sociodemographic determinants of COVID-19 incidence charges in Oman: geospatial modelling utilizing multiscale geographically weighted regression (MGWR). Sustainable Cities Soci. (2021) 65:102627. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102627

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Sannigrahi, S, Pilla, F, Basu, B, Basu, AS, and Molter, A. Examining the affiliation between socio-demographic composition and COVID-19 fatalities within the European area utilizing spatial regression method. Sustainable Cities Soci. (2020) 62:102418. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102418

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar