Katayon Karami

Katayon Karami

Born in Tehran in 1967, she studied structure on the Middle East Technical University in Ankara, Turkey, and for the reason that Nineties has developed a physique of labor that engages deeply with fashionable life and the complexities of Iranian society. Her artwork is rooted in private and social narratives, typically bearing on the state of affairs of ladies in Iran and drawing on collective experiences to discover broader problems with identification, visibility, and illustration.

Since 2002, Tehran-based Karami has exhibited his work in quite a few solo and group exhibitions all through Iran and overseas. She joined Kayhan Life for a dialog about her life and artwork.

Women’s social state of affairs performs a central position in your artwork. How do you go about expressing these themes by way of your work?

As an Iranian girl, my perspective inevitably intersects with gender, however I do not take into account it to be my sole focus. After the Green Movement of 2009, I created works that weren’t explicitly about girls, however had been deeply influenced by a collective ambiance. If I describe sure experiences, it’s as a result of they move by way of me, and they’re a lived actuality. It creates a female side to the work, nevertheless it’s not intentional. I’m only once I reply to feelings that I’ve personally skilled. That’s why I typically use combined media to depict the complexity of those multilayered truths.

How do you see the position of artwork in shaping social consciousness and dialogue, particularly concerning girls’s rights?

Art has a robust energy in shaping consciousness. This permits for a kind of engagement that can’t essentially be achieved by way of direct interplay. This is much more evident immediately with the fast unfold of photographs and movies on social media. Mahasa protest underway [the wave of demonstrations across Iran in 2022 after the death in police custody of Mahsa Amini]For instance, I used to be doing an exhibition in India, and coincidentally, quite a lot of the work I introduced with me explored themes of feminine identification and the veil. As information of Martha’s loss of life unfold world wide, younger Indian guests, a lot of whom had by no means been to an artwork exhibition earlier than, got here particularly as a result of they had been moved by what was occurring in Iran. That second deeply confirmed my perception within the potential of artwork to resonate throughout borders.

Even if a picture or work is finally forgotten, its visibility at key moments could make the distinction. It may change somebody’s perspective – and it already is smart to me. Personally, my encounters with sure works have deeply formed my worldview, and I hope to supply that chance to others by way of my very own follow.

What do you concentrate on the visibility of Iranian feminine artists within the international artwork scene?

In current years, I really feel that the worldwide recognition of Iranian artists, no matter gender, has sadly declined. There have been encouraging moments, resembling some artists collaborating in biennales or holding sturdy exhibitions overseas, however these stay the exception moderately than the norm. For instance, the visibility of Iranian cinema far exceeds the visibility of our nation’s visible arts scene.

That mentioned, the extra folks have interaction with the work and the deeper the dialogue round it, the extra visibility it could acquire. The alternative to speak about our artwork and contextualize it helps foster interpretive connections. While we’re grateful that a few of our work is seen past Iran’s borders, we want to see extra constant platforms, assist, and engagement that may elevate Iranian girls artists extra broadly on the world stage.

Can you inform us about your early influences and what led you to pursue artwork as a profession?

My early curiosity in artwork started at a really younger age once I attended a images class in Kanun in the course of the revolution. During this era, my household moved continuously and life felt unstable, however the darkroom turned a spot of calm. Seeing a picture emerge on paper was magical, and images turned a solution to course of the world.

I needed to go to Honarestan (artwork faculty), however my trainer stopped me as a result of I used to be good at math and physics. So I took a extra conventional path and later studied structure in Ankara. But it was throughout these first few months of sophistication visiting galleries and analyzing how areas are reworked by way of artwork that I actually started to know the depth and potential of visible language. I used to be fascinated by how artists suppose, how they assemble that means, and the way artwork can maintain emotion, reminiscence, and philosophy . These experiences formed my path to artwork. It wasn’t a one-time choice, however a gradual realization that that is how I perceive and talk with the world.

Red line, 2024.

Red line, 2024.

Image supplied by the artist.

You started your profession as an artist in Tehran within the Nineties, a interval of nice social and political change. How did that setting affect your work?

Since I had no formal coaching in images, I approached it extra intuitively. I used to be drawn to social points, even when they weren’t straight seen in my work. Loads of my early images was observational. I frequently roamed Tehran and the countryside, photographing life.

The large change got here after volunteering at a hospital after the Bam earthquake in 2003. I documented the destruction of cities with different photographers, nevertheless it was the hospitals and mass graves that had a huge impact on me. I noticed firsthand how fragile identities can change into in moments of disaster. That expertise led to my first self-portrait collection “Censored” (2004), the place I started utilizing images to handle social points extra deeply. It marked a shift from statement to a extra dialogic and emotionally pushed follow.

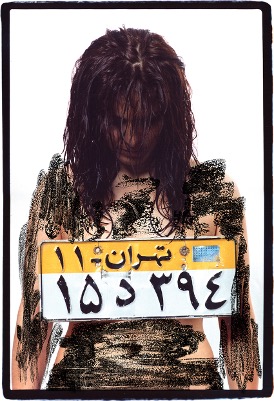

Censorship, 2004.

Censorship, 2004.

Image supplied by the artist.

How has your creative follow developed over time, from the Nineties to immediately?

My follow has modified considerably over the previous few years, from a extra observational follow within the Nineties to a deeply personally and socially engaged follow for the reason that 2009 inexperienced motion. Until then, I typically noticed myself as an observer, recording what I encountered with out absolutely understanding the long-term significance of that second. After 2009, I now not felt like I used to be simply taking photographs. I needed to ask the viewer into the emotional and political house I used to be navigating. My sensitivity to social points has grown stronger and I felt I wanted to replicate it in my work in a method that revered its complexity and urgency.

Since then, every mission has developed organically from the final. For instance, my “Resurrection” collection (2009) started after the executions at Evin Prison, which was one thing we desperately tried to forestall. On that day, a prostitute generally known as “Khorshid” who additionally murdered a new child child was executed. I went dwelling distraught and felt like I had to reply to that by creating this collection, nevertheless it nonetheless felt incomplete. Then, with Have a Break (2012), made in response to new reviews about executions, particularly the stoning of ladies, I felt I used to be lastly in a position to categorical what my earlier work had left unsaid.

You typically depict your self in your work. Do you take into account your self-presentation to be autobiographical, symbolic, or each? How has your portrayal of your self developed over time?

I do not usually consider my self-portraits as autobiographical. When I used to be youthful, I typically criticized myself just because the subjects I explored had been tough, and I did not need to contain others within the emotional weight of these subjects. However, over time, self-portraits turned greater than only a sensible possibility, they turned a visible language of narration that allowed for symbolism, emotion, and generally surreal reflection.

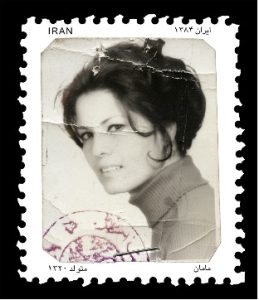

Stamp, 2005. Image supplied by the artist.

Stamp, 2005. Image supplied by the artist.

For instance, in works just like the Stamp (2005) collection, the usage of photographs of me and my mom is deeply condemned. Although these works might seem autobiographical, additionally they converse to collective recollections and shared experiences of struggle, revolution, state violence, pressured veiling, and systematic erasure. There is a continuity throughout generations in these experiences that I needed to make seen. While my photographs exist, they typically take the place of one thing bigger, resembling a communal voice, a shared historical past, or a silent resistance. Over time, I started to think about self-expression not simply as private reflection, however as a solution to join private reminiscence with collective trauma and resilience.

Click right here for particulars: https://katayounkarami.com