1 Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), attributable to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has profoundly impacted international well being since its emergence in late 2019 (1–4). The pandemic has led to important morbidity and mortality worldwide, overwhelming healthcare programs and disrupting economies (5, 6). With hundreds of thousands of confirmed circumstances and deaths, COVID-19 has highlighted the vulnerability of world well being infrastructures to rising infectious illnesses (7, 8). The virus’s fast unfold and excessive transmissibility have necessitated unprecedented public well being measures, together with lockdowns, social distancing, and mass vaccination campaigns, to mitigate its influence (9–11).

The pandemic has unfolded in a number of waves, every characterised by completely different variants of the virus, various ranges of transmissibility, and distinct patterns of morbidity and mortality (12). These waves have positioned immense strain on healthcare sources and have been related to important fluctuations in case numbers and healthcare demand (13). The emergence of recent variants, akin to B.1.617.2 and B.1.1.529, has sophisticated efforts to manage the pandemic, with every variant posing distinctive challenges when it comes to transmissibility, vaccine effectiveness, and illness severity (14).

In Iran, the burden of COVID-19 has been substantial, with the nation experiencing a number of waves of an infection which have strained its healthcare system. High charges of an infection and mortality have been reported, notably through the peaks of the pandemic (15). The Iranian healthcare system has confronted quite a few challenges, together with shortages of medical provides, overwhelmed hospitals, and difficulties in implementing public well being measures (16). Despite these challenges, efforts have been made to boost testing, remedy, and vaccination to manage the unfold of the virus and cut back its influence on the inhabitants.

Despite in depth international analysis on COVID-19, understanding reinfection, notably its medical implications and related variants, stays restricted. Given the excessive burden of COVID-19 in Iran and the evolving nature of the virus, it’s essential to research SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in on this particular demographic. The intention of this examine was to determine the speed and the chance elements related to SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and evaluate the medical course of preliminary an infection versus reinfection in readmitted COVID-19 sufferers in Iran.

2 Materials and strategies

2.1 Study design

2.2 Diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2

2.3 Data assortment

Data assortment was performed utilizing a research-made guidelines by the principal investigator. Data had been collected from the built-in digital well being system of the hospitals and the medial report database. Demographic knowledge, together with age, intercourse, and the presence of underlying medical situations akin to hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), cardiovascular illnesses, and most cancers, had been collected. The vaccination standing and the standing of receiving the vaccine booster dose of sufferers was recorded, and sufferers had been categorised into two teams: those that had been absolutely vaccinated [received two doses of vaccine (20)] and people who weren’t absolutely vaccinated. The medical signs had been categorised into two classes based mostly on the chief criticism of sufferers at admission: frequent signs of SARS-CoV-2 an infection, together with cough, fever, shortness of breath, sore throat, fatigue, and myalgia; and fewer frequent signs, akin to diarrhea, joint ache, and neurological problems (21). Laboratory parameters, together with white blood cell (WBC) rely, Interleukin-6 (IL-6) ranges, and C-reactive protein (CRP) ranges, had been additionally gathered. Moreover, the period of their intensive care unit (ICU) and hospital stays, in addition to their mortality through the admission interval, had been documented. When out there, knowledge on the variant of SARS-CoV-2 answerable for the an infection had been additionally collected.

2.4 Statistical evaluation

Data had been analyzed utilizing SPSS model 25. After calculating the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection charge by dividing the variety of reinfection circumstances by the whole variety of admitted sufferers, the quantitative knowledge had been introduced as imply and commonplace deviation, whereas qualitative knowledge had been expressed as frequency and proportion. Comparisons had been made between the reinfection group and the management (non-reinfection) group. The unbiased pattern t-test and Chi-square check had been used to check quantitative and qualitative knowledge, respectively. Risk elements for reinfection had been evaluated via univariable and multivariable regression fashions. To guarantee a balanced comparability between the medical course and medical outcomes of the reinfected and non-reinfected teams, propensity rating matching (PSM) was performed based mostly on baseline demographic variables, together with age, intercourse, and underlying illness. The matching was carried out in a 1:1 ratio utilizing R software program. A p-value lower than 0.05 thought-about as important.

2.5 Ethical concerns

The examine was performed in accordance with moral requirements and pointers to make sure the safety and confidentiality of affected person data. Informed consent was waived by the ethics committee as a result of retrospective nature of the examine, which concerned the evaluation of present medical information with out direct affected person interplay. To keep confidentiality, all affected person knowledge had been anonymized and saved securely. Access to the info was restricted to the analysis crew members who had been immediately concerned within the examine. Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.BMSU.REC.1400.159).

3 Results

3.1 Demographic knowledge

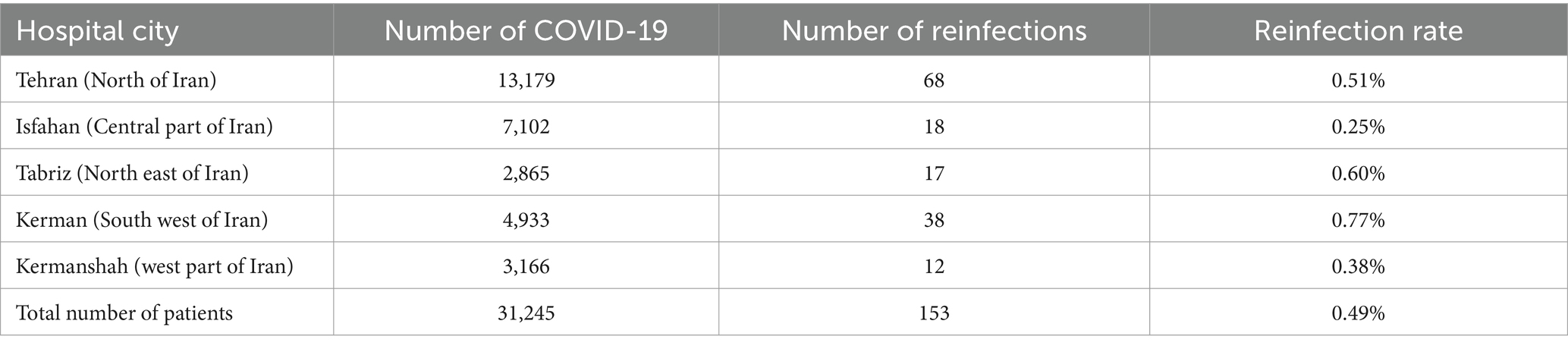

A complete of 31,245 sufferers with confirmed circumstances of SARS-CoV-2 an infection from 5 hospitals in Tehran, Isfahan, Tabriz, Kerman, and Kermanshah had been included within the closing evaluation to find out the speed of reinfection. Of these sufferers, 153 (0.49%) skilled reinfections based mostly on the examine standards. Table 1 presents the standing of reinfection in numerous hospitals and areas of Iran. The imply age of sufferers with reinfection was 54.5 ± 12.5 years, whereas the imply age in sufferers with out confirmed reinfection was 62.3 ± 13.6 years (p < 0.001). Among the 153 sufferers, 128 (83.7%) had been male and 25 (16.3%) had been feminine. The intercourse distribution was considerably completely different between the reinfection group and the management group (p < 0.001). The demographic knowledge are introduced in Table 1.

Table 1. The charge of reinfection in numerous components of Iran.

3.2 Clinical, laboratory and end result knowledge

A complete of 112 (73.2%) sufferers with reinfection reported at the very least one underlying situation akin to diabetes, weight problems, pulmonary illness, or heart problems (p = 0.041). In addition, 53 sufferers (34.6%) within the reinfection group had a full historical past of vaccination, whereas the variety of absolutely vaccinated sufferers in sufferers with out reinfection was 18,033 sufferers (57.9%, p < 0.001). Reinfection circumstances had been extra prone to current with atypical signs, whereas in sufferers with out reinfection, COVID-19 typically manifested with typical signs (p < 0.001). In the evaluation of laboratory values, sufferers with solely major an infection had important decrease WBC rely in comparison with sufferers within the reinfection group (8.5 ± 2 vs. 6.5 ± 2; p < 0.001). In addition, CRP and IL-6 ranges had been additionally considerably increased in major SARS-CoV-2 an infection (50 ± 20 vs. 30 ± 20; p < 0.001; and 40 ± 18 vs. 25 ± 15; p < 0.001, respectively). Primary SARS-CoV-2 an infection resulted in longer ICU admissions in comparison with reinfections (5 ± 4 vs. 12 ± 10; p < 0.001). Also, sufferers with reinfection had shorter course of total hospital keep (7 ± 6 vs. 16 ± 21; p < 0.001). Table 2 presents the medical knowledge of COVID-19 between the reinfection group and the management group.

Table 2. Clinical, laboratory and end result knowledge of sufferers with reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and the management group.

3.3 Risk elements of reinfection

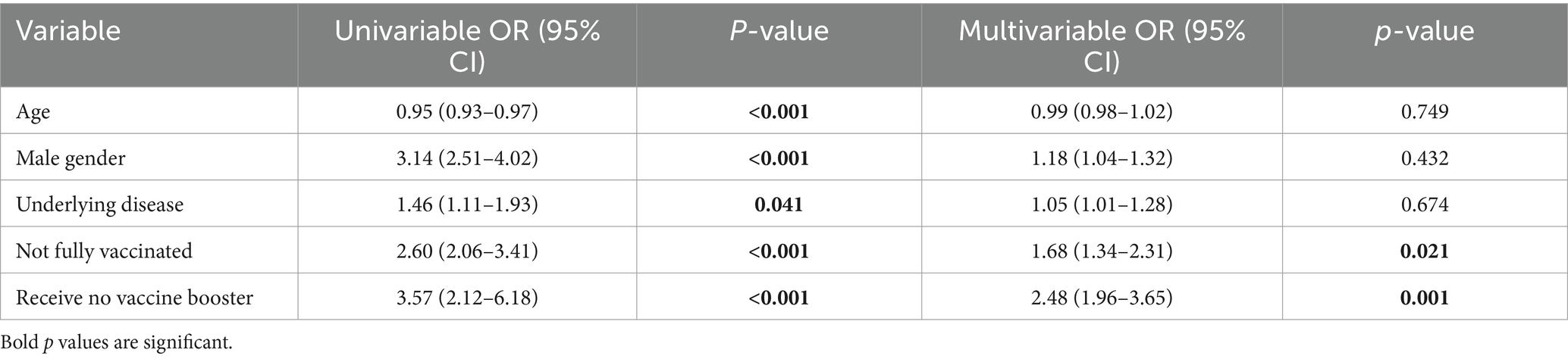

In the univariable evaluation, age was discovered to be a big issue, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.95 (95% CI: 0.93–0.97; p < 0.001). Males had considerably increased odds of reinfection, with an OR of three.14 (95% CI: 2.51–4.02; p < 0.001). The presence of an underlying illness additionally confirmed a statistically important affiliation with reinfection threat, with an OR of 1.46 (95% CI: 1.11–1.93; p = 0.041). Vaccination standing was strongly related to reinfection threat, with an OR of two.60 (95% CI: 2.06–3.41; p < 0.001). Additionally, vaccine booster standing was probably the most important predictor within the univariable evaluation, with an OR of three.57 (95% CI: 2.12–6.18; p < 0.001). After adjusting for potential confounders within the multivariable logistic regression mannequin, vaccination remained a big predictor of decreased reinfection threat (OR: 1.68, 95% CI: 1.34–2.31; p = 0.021). Also, vaccine booster standing continued to be probably the most important issue related to reinfection, with those that didn’t obtain a booster having an OR of two.48 (95% CI: 1.96–3.65; p = 0.001). The outcomes of the regression evaluation are introduced in Table 3.

Table 3. Risk elements of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

3.4 Propensity rating matching

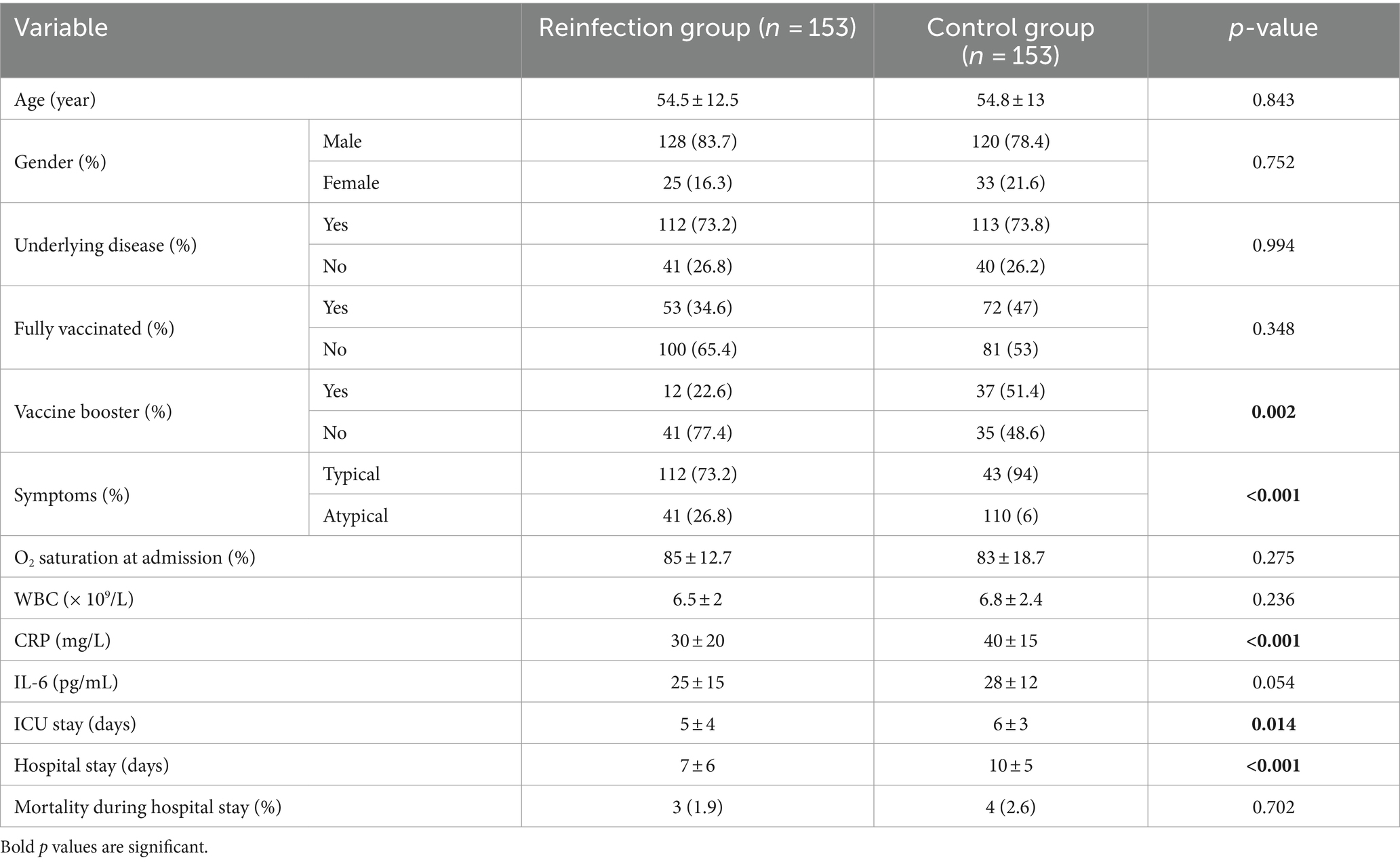

After propensity rating matching based mostly on age, intercourse, and likewise underlying illness, atypical signs had been considerably increased in sufferers with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection (26.8% vs. 6%; p < 0.001). In addition, the extent of CRP in these sufferers was considerably decrease than in sufferers within the management group (30 ± 20 vs. 40 ± 15; p < 0.001). Patients within the management group had an extended course of ICU keep (6 ± 3 vs. 5 ± 4; p = 0.014) and the hospital keep was considerably longer in management group (10 ± 5 vs. 7 ± 6; p < 0.001). There had been no important variations when it comes to vaccination standing, O2 saturation at admission, WBC, IL-6 and likewise mortality throughout hospital keep between the 2 teams (p = 0.702). Table 4 urged the outcomes after PSM.

Table 4. Clinical, laboratory and end result knowledge of sufferers with reinfection of SARS-CoV-2 and the management group after PSM.

3.5 Different dates and COVID-19 waves

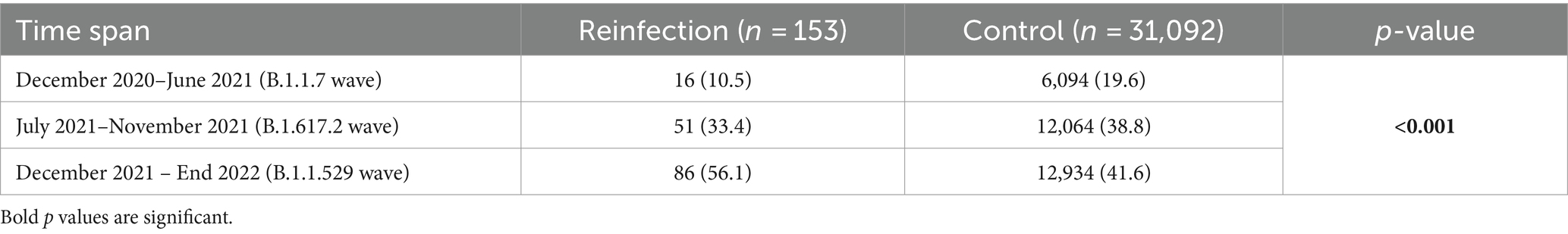

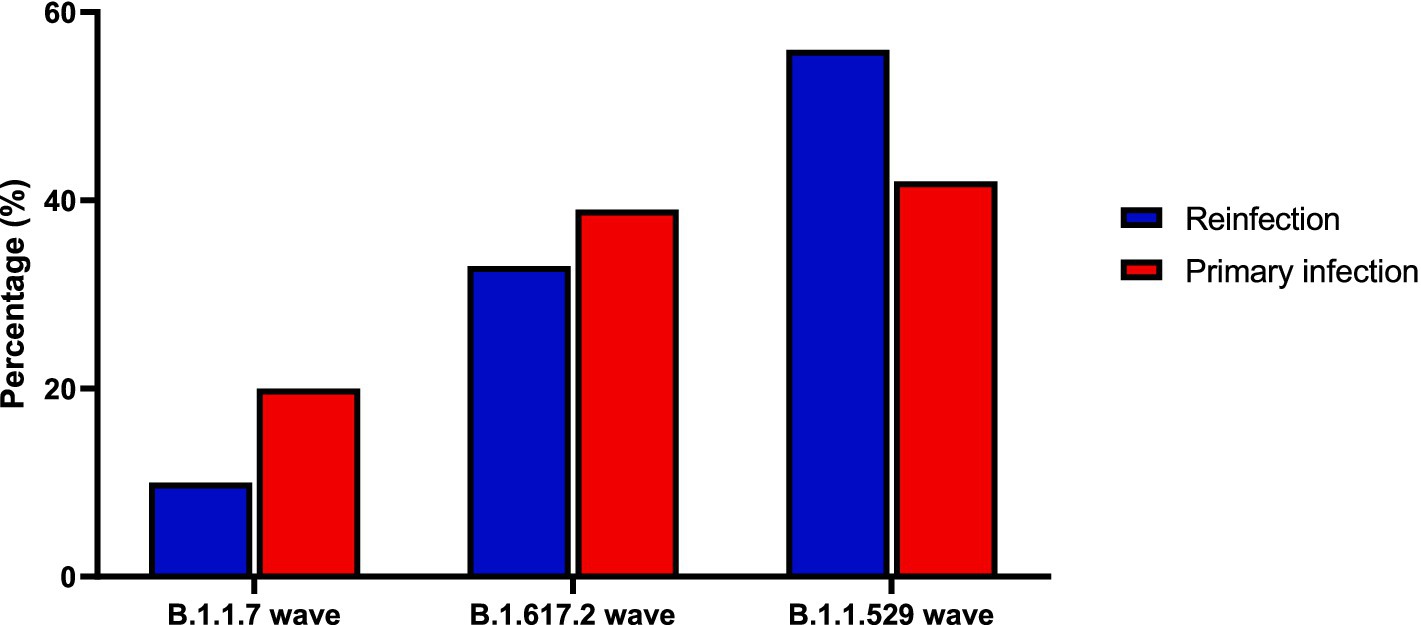

Table 5 and Figure 1 present the distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants within the reinfection and management teams over three completely different time intervals similar to the B.1.1.7, B.1.617.2, and B.1.1.529 waves. During the B.1.1.7 wave (December 2020–June 2021), 10.5% of reinfection circumstances occurred in comparison with 19.6% of sufferers within the management group. In the B.1.617.2 wave (July 2021–November 2021), 33.4% of reinfections occurred in comparison with 38.8% of sufferers within the management group. During the B.1.1.529 wave (December 2021 – finish of 2022), 56.1% of reinfections had been recorded, in comparison with 41.6% of sufferers within the management group. The total distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants within the reinfected and management teams suggests a shift towards a better chance of reinfection from B.1.1.7 to B.1.1.529 wave. The chi-squared check means that reinfections had been extra prone to happen during times of recent SARS-CoV-2 variants such because the B.1.1.529 and the B.1.617.2 variants (p < 0.001).

Table 5. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants amongst reinfection and management group throughout completely different waves.

Figure 1. Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants amongst reinfection and management group throughout completely different waves.

3.6 Different SARS-CoV-2 variants

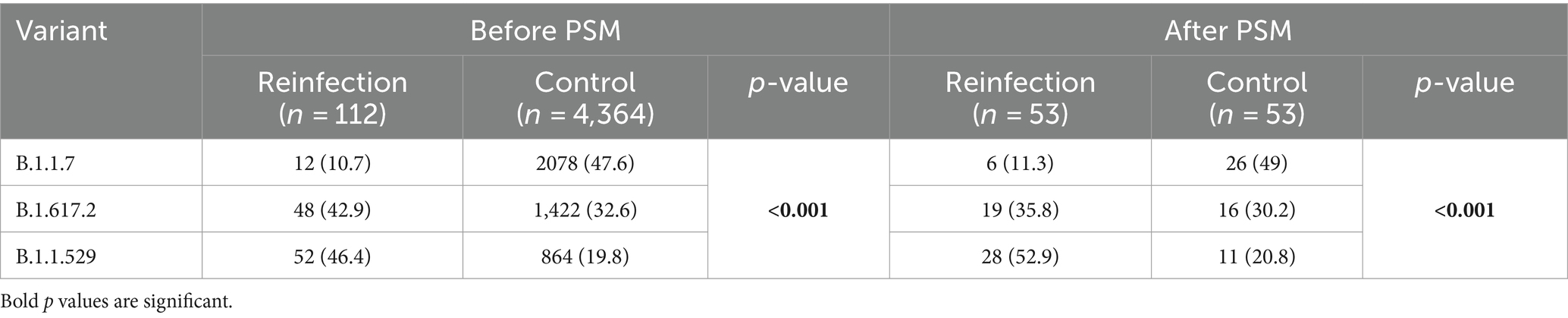

The knowledge for SARS-CoV-2 variants had been current in 112 sufferers (73.2%) within the reinfection group and 4,364 sufferers (14%) within the management group. It was urged that sufferers within the management group had considerably increased distribution of B1.1.7 variant whereas the reinfection group had extra B1.1.529 variants. After propensity rating matching based mostly on age, intercourse, and likewise underlying illness, 53 sufferers remained in each teams. Same because the outcomes earlier than PSM, the B.1.617.2 and the B.1.1.529 variants had been extra prevalent within the reinfection group whereas the B.1.1.7 variant was extra prevalent within the management group (p < 0.001). The outcomes for SARS-CoV-2 variants in each teams are introduced in Table 6.

Table 6. SARS-CoV-2 variants in reinfection and management group earlier than and after PSM.

4 Discussion

The outcomes of our examine point out that among the many 0.5% of circumstances that met the WHO standards for reinfection, these people had milder illness manifestations and a milder medical course than these with major infections. It has been urged that reinfection is extra pronounced within the new wave of SARS-CoV-2 variants and that full vaccination, particularly booster vaccination, could also be efficient in stopping reinfection. It is noteworthy that the B.1.1.529 variant was extra prevalent amongst those that had skilled reinfection. These findings contribute considerably to our understanding of virus dynamics and inform ongoing efforts in public well being methods, notably within the context of rising variants and vaccine efficacy.

It is essential to differentiate between a reinfection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the illness and a return of signs. These two situations may be difficult points in medical observe (22). The prognosis of reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is complicated. Reinfection can typically be overreported based mostly on medical signs or radiological findings, and in some circumstances, PCR assessments could be destructive regardless of an energetic an infection (23). In such situations, sufferers may expertise a relapse of the unique an infection, or they might produce other illnesses with signs just like SARS-CoV-2, akin to influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (24). In addition, many people experiencing reinfection might not search medical consideration or might solely go to outpatient clinics, thus not being captured in hospital-based knowledge (25). The present examine assumed a reinfection charge of 0.5%. This result’s per earlier research within the present literature. In the meta-analysis of 23 research in 2023, the reinfection charge ranged from 0.1 to six.8% (26). In addition, in a current meta-analysis in 2024, the pooled charge of reinfection in 55 research was estimated to be 0.94% (27). The noticed distinction within the reported charge of reinfection could also be primarily as a consequence of variations in affected person choice standards. In our examine, we made a concerted effort to rigorously choose sufferers in a way that minimized the chance of false positives whereas adhering to WHO pointers.

Our outcomes align with earlier research suggesting that reinfections typically current with much less extreme outcomes in comparison with major infections (28). The commentary that circumstances of reinfection had shorter hospital and ICU stays is per different reviews indicating that immune responses from prior infections or vaccinations may cut back the severity of subsequent infections (29). Furthermore, the discrepancy within the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variants between reinfection and first an infection circumstances highlights the virus’s evolving nature and its influence on illness presentation (30). The decrease frequency of full vaccination in reinfected people in comparison with the non-reinfected group additionally underscores the necessity for continued analysis into the effectiveness of present vaccines towards rising variants (31). Although this distinction was not statistically important following PSM, it stays crucial to proceed evaluating vaccine efficacy, notably within the context of rising variants. The effectiveness of vaccines towards variants has been proven to decrease over time, necessitating booster doses to take care of protecting immunity (32). Our examine’s findings are per the literature, which signifies that whereas vaccines stay efficient in stopping extreme illness, the evolving nature of SARS-CoV-2 variants calls for normal updates to vaccination protocols and booster suggestions (33).

The distribution of SARS-CoV-2 variants within the reinfection and management teams highlighted a transparent pattern towards a better proportion of reinfections throughout waves dominated by newer variants. Reinfections had been much less frequent through the B.1.1.7 wave. This pattern shifted considerably with the emergence of the B.1.617.2 variant and have become much more pronounced through the B.1.1.529 wave. The rising reinfection charge in later waves is per the immune-evading properties of newer variants akin to B.1.1.529, which have been proven to have increased transmissibility and decreased vaccine efficacy (34). Studies have proven that B.1.1.529, with its quite a few spike protein mutations, is more proficient at escaping each pure immunity and vaccine-induced immunity, resulting in elevated reinfection charges (35). Our evaluation additionally demonstrated that people who obtained a vaccine booster had been considerably much less prone to expertise reinfection, even through the B.1.1.529 wave, highlighting the constructive impact of booster doses in enhancing safety towards immune-evading variants. This is additional supported by research exhibiting that booster doses can restore vaccine efficacy towards variants akin to B.1.1.529 (36).

It is vital to acknowledge the restrictions of our examine, regardless of its sturdy design. The first limitation is the reliance on PCR testing as the only technique for confirming SARS-CoV-2 an infection, which can not seize all circumstances, notably these with low viral hundreds the place PCR sensitivity could be decreased. This may probably result in an underestimation of reinfection charges. However, by specializing in constructive PCR outcomes, we ensured diagnostic certainty and accuracy in figuring out true reinfection circumstances. Another important problem encountered on this examine was the restricted entry to diagnostic kits for SARS-CoV-2 variant identification in Iran. Due to sanctions, these kits had been continuously unavailable or in brief provide, which constrained our capability to precisely determine particular variants. Additionally, lots of the reinfection circumstances occurred after the introduction of variant-specific diagnostic kits, whereas a big portion of the management circumstances had been from a interval when new variants had not but been recognized. Consequently, variant knowledge, notably within the management group, might have been underrepresented. To deal with this imbalance and guarantee a strong comparability between the 2 teams, we utilized PSM. Another limitation is the dearth of detailed knowledge on remedy situations. Although there are established pointers for COVID-19 remedy, the remedy protocols modified over the pandemic time (37). In addition, the administration of administration methods diverse relying on the supply of prescription drugs and the limitation of sources in numerous cities and medical facilities. The final limitation of our examine is the dearth of prolonged follow-up knowledge. Although reinfections typically current with milder signs, they could be related to extreme long-term problems akin to stroke, myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism (38).

This examine recommends prioritizing revaccination campaigns to enhance safety towards reinfection with SARS-CoV-2, particularly within the face of rising immune-evading variants akin to B.1.1.529. Public well being methods must be frequently up to date to replicate the evolving nature of the virus, and efforts should be made to enhance entry to variant-specific diagnostic instruments in resource-limited settings. In addition, future analysis ought to concentrate on longer-term follow-up to evaluate potential problems of reinfection, akin to cardiovascular occasions, to offer a extra complete understanding of the long-term results of SARS-CoV-2.

5 Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 reinfection typically exhibited milder signs and shorter hospital stays than major infections. Novel SARS-CoV-2 variants had been extra frequent amongst reinfected people. Although vaccination may also help forestall reinfection, the complicated relationship between vaccination and reinfection highlights the necessity for additional analysis. Future research are wanted to evaluate the long-term problems of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

Data availability assertion

Ethics assertion

The research involving people had been authorized by Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Ethics code: IR.BMSU.REC.1400.159). The research had been performed in accordance with the native laws and institutional necessities. The individuals supplied their written knowledgeable consent to take part on this examine.

Author contributions

MSh: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal evaluation, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – unique draft, Writing – overview & modifying. YA: Formal evaluation, Methodology, Software, Writing – overview & modifying. RY: Data curation, Resources, Writing – overview & modifying. MSa: Methodology, Validation, Writing – overview & modifying. MI: Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – overview & modifying. MR: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal evaluation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – unique draft, Writing – overview & modifying.

Funding

Acknowledgments

Thanks to steering and recommendation from the “Clinical Research Development Unit of Baqiyatallah Hospital”.

Conflict of curiosity

Publisher’s observe

Abbreviations

References

1. Shahrbaf, MA, Tabary, M, and Khaheshi, I. Cardiovascular concerns of Remdesivir and Favipiravir within the remedy of COVID-19. Cardiovasc Haematol Disord Drug Targets. (2021) 21:88–90. doi: 10.2174/1871529X21666210812103535

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Barekat, M, Shahrbaf, MA, Rahi, Okay, and Vosough, M. Hypertension in COVID-19, a threat issue for an infection or a late consequence? Cell J. (2022) 24:424. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2022.8487

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Robat-Jazi, B, Ghorban, Okay, Gholami, M, Samizadeh, E, Aghazadeh, Z, Shahrbaf, MA, et al. β-D-mannuronic acid (M2000) and inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19; an in vitro examine. Iran J Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2022) 21:677–86. doi: 10.18502/ijaai.v21i6.11528

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Shahrbaf, MA, Hassan, M, and Vosough, M. COVID-19 and hygiene speculation: increment of the inflammatory bowel illnesses in subsequent technology? Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2022) 16:1–3. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2022.2020647

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

7. Tehrani, S, Fekri, S, Demirci, H, Nourizadeh, AM, Kashefizadeh, A, Shahrbaf, MA, et al. Coincidence of candida endophthalmitis, and aspergillus and pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in a COVID-19 affected person: case report. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. (2023) 31:1291–4. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2023.2188224

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

8. Zarrabi, M, Shahrbaf, MA, Nouri, M, Shekari, F, Hosseini, S-E, Hashemian, S-MR, et al. Allogenic mesenchymal stromal cells and their extracellular vesicles in COVID-19 induced ARDS: a randomized managed trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2023) 14:169. doi: 10.1186/s13287-023-03402-8

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

9. Raei, M, Shahrbaf, MA, Salaree, MM, Yaghoubi, M, and Parandeh, A. Prevalence and predictors of burnout amongst nurses through the COVID-19 pandemic: a survey in educating hospitals. Work. (2023) 77:1049–57. doi: 10.3233/WOR-220001

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Shahrbaf, MA, Nasr, DS, and Langroudi, ZT. COVID-19 and well being selling hospitals in Iran; what can we stand? International journal of preventive drugs. Int J Prev Med. (2022) 13:13–125. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.ijpvm_492_21

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

12. El-Shabasy, RM, Nayel, MA, Taher, MM, Abdelmonem, R, Shoueir, KR, and Kenawy, ER. Three waves adjustments, new variant strains, and vaccination impact towards COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Biol Macromol. (2022) 204:161–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.01.118

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Moynihan, R, Sanders, S, Michaleff, ZA, Scott, AM, Clark, J, To, EJ, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on utilisation of healthcare providers: a scientific overview. BMJ Open. (2021) 11:e045343. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045343

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Dhama, Okay, Nainu, F, Frediansyah, A, Yatoo, MI, Mohapatra, RK, Chakraborty, S, et al. Global rising omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2: impacts, challenges and methods. J Infect Public Health. (2023) 16:4–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2022.11.024

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Heidari, M, Sayfouri, N, and Jafari, H. Consecutive waves of COVID-19 in Iran: numerous dimensions and possible causes. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. (2022) 17:e136. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2022.45

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Khankeh, H, Farrokhi, M, Roudini, J, Pourvakhshoori, N, Ahmadi, S, Abbasabadi-Arab, M, et al. Challenges to handle pandemic of coronavirus illness (COVID-19) in Iran with a particular scenario: a qualitative multi-method examine. BMC Public Health. (2021) 21:1919. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11973-5

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Chisale, MRO, Sinyiza, FW, Kaseka, PU, Chimbatata, CS, Mbakaya, BC, Wu, TJ, et al. Coronavirus illness 2019 (COVID-19) reinfection charges in Malawi: a doable software to information vaccine prioritisation and immunisation insurance policies. Vaccines. (2023) 11:1185. doi: 10.3390/vaccines11071185

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Dip, SD, Sarkar, SL, Setu, MAA, Das, PK, Pramanik, MHA, Alam, A, et al. Evaluation of RT-PCR assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Sci Rep. (2023) 13:2342. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-28275-y

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Ntagereka, PB, Oyola, SO, Baenyi, SP, Rono, GK, Birindwa, AB, Shukuru, DW, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 reveals various mutations in circulating alpha and Delta variants through the first, second, and third waves of COVID-19 in south Kivu, east of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Int J Infect Dis. (2022) 122:136–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.05.041

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

20. Seo, WJ, Kang, J, Kang, HK, Park, SH, Koo, HK, Park, HK, et al. Impact of prior vaccination on medical outcomes of sufferers with COVID-19. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2022) 11:1316–24. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2022.2069516

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Adhikari, SP, Meng, S, Wu, Y-J, Mao, Y-P, Ye, R-X, Wang, Q-Z, et al. Epidemiology, causes, medical manifestation and prognosis, prevention and management of coronavirus illness (COVID-19) through the early outbreak interval: a scoping overview. Infect Dis Poverty. (2020) 9:29. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00646-x

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Phan, T, Tran, NYK, Gottlieb, T, Siarakas, S, and McKew, G. Evaluation of the influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) targets within the AusDiagnostics SARS-CoV-2, influenza and RSV 8-well assay: pattern pooling will increase testing throughput. Pathology. (2022) 54:466–71. doi: 10.1016/j.pathol.2022.02.002

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Azam, M, Pribadi, FS, Rahadian, A, Saefurrohim, MZ, Dharmawan, Y, Fibriana, AI, et al. Incidence of COVID-19 reinfection: an evaluation of outpatient-based knowledge within the United States of America. medRxiv. (2021) 2021:7206. doi: 10.1101/2021.12.07.21267206

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Nguyen, NN, Nguyen, YN, Hoang, VT, Million, M, and Gautret, P. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and severity of the illness: a scientific overview and Meta-analysis. Viruses. (2023) 15:967. doi: 10.3390/v15040967

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

27. Chen, Y, Zhu, W, Han, X, Chen, M, Li, X, Huang, H, et al. How does the SARS-CoV-2 reinfection charge change over time? The international proof from systematic overview and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. (2024) 24:339. doi: 10.1186/s12879-024-09225-z

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Deng, J, Ma, Y, Liu, Q, Du, M, Liu, M, and Liu, J. Severity and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection in contrast with major an infection: a scientific overview and Meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2023) 20:3335. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043335

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

29. de La Vega, MA, Polychronopoulou, E, Xiii, A, Ding, Z, Chen, T, Liu, Q, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced immunity reduces charges of reinfection and hospitalization attributable to the Delta or omicron variants. Emerg Microbes Infect. (2023) 12:e2169198. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2023.2169198

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Manirambona, E, Okesanya, OJ, Olaleke, NO, Oso, TA, and Lucero-Prisno, DE. Evolution and implications of SARS-CoV-2 variants within the post-pandemic period. Discover Public Health. (2024) 21:16. doi: 10.1186/s12982-024-00140-x

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Gómez-Gonzales, W, Chihuantito-Abal, LA, Gamarra-Bustillos, C, Morón-Valenzuela, J, Zavaleta-Oliver, J, Gomez-Livias, M, et al. Risk elements contributing to reinfection by SARS-CoV-2: a scientific overview. Adv Respir Med. (2023) 91:560–70. doi: 10.3390/arm91060041

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Dadras, O, SeyedAlinaghi, S, Karimi, A, Shojaei, A, Amiri, A, Mahdiabadi, S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccines’ safety over time and the necessity for booster doses; a scientific overview. Arch Acad Emerg Med. (2022) 10:e53. doi: 10.22037/aaem.v10i1.1582

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Hogan, AB, Doohan, P, Wu, SL, Mesa, DO, Toor, J, Watson, OJ, et al. Estimating long-term vaccine effectiveness towards SARS-CoV-2 variants: a model-based strategy. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:4325. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39736-3

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

34. He, X, Hong, W, Pan, X, Lu, G, and Wei, X. SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant: traits and prevention. MedComm. (2021) 2:838–45. doi: 10.1002/mco2.110

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Pulliam, JRC, van Schalkwyk, C, Govender, N, von Gottberg, A, Cohen, C, Groome, MJ, et al. Increased threat of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection related to emergence of omicron in South Africa. Science. (2022) 376:abn4947. doi: 10.1126/science.abn4947

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Bar-On, YM, Goldberg, Y, Mandel, M, Bodenheimer, O, Amir, O, Freedman, L, et al. Protection by a fourth dose of BNT162b2 towards omicron in Israel. N Engl J Med. (2022) 386:1712–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201570

Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Wu, Y, Feng, X, Gong, M, Han, J, Jiao, Y, Li, S, et al. Evolution and main adjustments of the prognosis and remedy protocol for COVID-19 sufferers in China 2020–2023. Health Care Sci. (2023) 2:135–52. doi: 10.1002/hcs2.45

PubMed Abstract | Crossref Full Text | Google Scholar